This past week on my Tumblr, I’ve been posting one of my favorite Bob Dylan songs each day in honor of the man’s 70th birthday. For the most part, these aren’t the same tired handful of tracks that get pulled out every time. And as an added bonus, you can also read my sketchy theories and poorly edited ramblings! For the full rundown from the beginning, click here.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged bob dylan, bob dylan and the band, music, tumblr biz | Leave a Comment »

One year ago today, I rode the 1 train downtown from the Upper West Side hostel where I had been staying and moved into my first ever New York apartment. Well, “apartment” may be generous (see photo evidence above*). As some of you know, I live in a women’s residence run as a charitable mission by an order of Catholic nuns. At the time, I thought I’d only be here a few months. Soon, I’d find a regular job and be able to afford a studio apartment of my own, one with a bathroom and a kitchen and air conditioning. Of course, things never work out as intended, and I’m still here. But I’ve gotten used to the minor inconveniences of living in confined quarters, operating under someone else’s rules. (To wit: no visitors allowed, so this photo is the first time most people will have seen my room.) It’s a small sacrifice to live in one of the best neighborhoods of one of the best cities in the world, and I’m grateful to the Sisters for taking me in. A year in, it’s easy to take New York for granted, but where else in the world would I rather be?

(Answer: NOWHERE)

*dim fluorescent ring bulb + no white balance = a photo that looks like it was taken in 1968. But at least you see three walls and the door frame. I’m also not allowed to put anything on the walls, but there’s no rule against festive curtains!

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged apartment, new york city | 1 Comment »

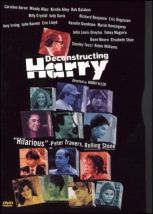

Age difference between Woody Allen (Harry Block) and his co-stars:

1) Bob Balaban (Richard, Harry’s best friend): 10 years

2) Kirstie Alley (Joan, Harry’s ex-wife): 16 years

3) Caroline Aaron (Doris, Harry’s sister): 17 years

4) Judy Davis (Lucy, Harry’s ex-girlfriend): 20 years

5) Elisabeth Shue (Fay, Harry’s current girlfriend): 28 years

Non-white actors with speaking parts:

1) Hazelle Goodman (Cookie, a prostitute)

2) Sunny Chae (Lily Chang, a prostitute)

I bring these figures up not because they are easy targets (although, admittedly, they are), or because I’m accusing Woody Allen of being racist or sexist or whatever, but because at this point it’s just so ridiculous and kind of exhausting, at least in the sense of “here we go again, another Woody Allen movie that’s a tribute to Woody Allen, and hey isn’t constantly talking about oneself, even negatively, a symptom of some sort of personality disorder, so why am I spending my time and money, both of which are limited in this one and only shot I have on Earth, on getting my ear jawed off by the type of person I’d cross the street to avoid in real life?” (And if I find Allen’s characters’ relationships with much-younger women gross, doesn’t that just make me an ageist, and don’t I then have no moral authority in this argument?)

Selected narcissistic traits, as listed on Wikipedia:

–An obvious self-focus in interpersonal exchanges

-Problems distinguishing the self from others (see narcissism and boundaries)

-Hypersensitivity to any sleights or imagined insults (see criticism and narcissists, narcissistic rage and narcissistic injury)

-Vulnerability to shame rather than guilt

-Detesting those who do not admire him or her

-Inability to view the world from the perspective of other people

-Belief that others actually read your blog, site stats to the contrary

My preferred types of Woody Allen movies (ranked in descending order):

1) Movies where Allen is off-screen (e.g., The Purple Rose of Cairo)

2) Movies where Allen has only a minor role (e.g., Hannah and Her Sisters)

3) The gimmicks (e.g., Zelig)

4) Movies with Diane Keaton (e.g., Manhattan)

***

5) All other Woody Allen movies

(Note: Allen’s pre-Annie Hall filmography is a personal blind spot. Will rectify eventually.)

Deconstructing Harry fits snugly in category 3, as it’s a meta-narrative – and a whole two years before Being John Malkovich made postmodernism trendy in indie film. Harry Block is a writer, by which I mean an author of literary fiction and not a screenwriter, and the film deconstructs his short stories and novels to reveal the real-life sources (“real-life” within the life of the movie, although, naturally, by drawing attention to the very concept of deconstruction, Allen is inviting us to also consider the relationship of his art to real-real life). What may have been yet another Allen relationship dramedy is reinvigorated by having a thematic anchor – OK, a gimmick – that forces Allen to focus while at the same time giving him some fresh ideas to play with. That’s also what makes it the probably “last good Woody Allen movie,” although to be fair I haven’t seen most of the movies he’s released since. The ones I have (Match Point, Vicky Cristina Barcelona) are category 1 entries, and thus aren’t really “Woody Allen movies” in the understood sense. And he has made more gimmick movies (Melinda and Melinda, for instance) that haven’t gotten good notices, so maybe my already shaky theory’s off-base anyway.

Movies in my Netflix queue ahead of Deconstructing Harry:

1) GasLand

2) The King of Marvin Gardens

3) Bringing Out the Dead

Reason those four movies were at the top of my queue:

1) Their Netflix status is listed as “Very Long Wait.”

2) I’d like to see them eventually.

I’m sorry if I’ve seemed kind of down on the guy, because I actually quite liked Deconstructing Harry! Still, it took me about half of the movie to get past all of my usual anti-Allenisms, and I never got completely over them. But looking over the list of Allen’s movies, there’s none that I’ve seen that I actually hate. Well, What’s Up Tiger Lily?, but no one likes that one. (There’re also several I‘d call overrated, but even those I enjoyed to some degree.) Part of this is surely self-selection – I avoid those Woody Allen movies I suspect I’ll find unbearable – but I think it also betrays the fact that, maybe, sorta, I have some degree of affection for the Woody Allen persona hiding beneath that vague repulsion? Would I have liked Deconstructing Harry more if, say, Albert Brooks (12 years younger than Allen and without all the baggage) was in the lead? Maybe! Would I like to revisit Allen in another lead role post-Deconstructing Harry? Not really! Do I have some catching up to do with Allen’s filmography. Oh, probably. One day.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 1997, 1997 movies, deconstructing harry, mailbox film festival, movies, woody allen | 3 Comments »

Over last Christmas break, I was talking to my dad about the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit. He made the comment that it didn’t feel like a typical Coen Brothers movie. I disagree, but I see where he was coming from. Mention the Coen Brothers and most people will think of Raising Arizona, Fargo, The Big Lebowski and Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?, films populated by broad characters but tempered by a dry, often quite dark, sense of humor. But the brothers have also crafted a parallel filmography of relatively straight-faced, noir-tinged thrillers. The precedent for True Grit can be found in past outings like Miller’s Crossing, No Country for Old Men, The Man Who Wasn’t There and Blood Simple. Most of these pictures do have their little gags – True Grit has its Bear Man – but their relation to the brothers’ comedies is one of philosophy, not of tone.

Ah, but what if someone were to remake one of those serious crime dramas but, you know, Coens it up a bit? Thus A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop, Chinese director Zhang Yimou’s recasting of the Coens’ debut Blood Simple as a wacky farce. Zhang cranks the Laff-o-Meter so hard that the needle soars past the goofier likes of Burn After Reading and The Ladykillers and pings straight into Manic Jerry Lewis territory. Curiously, Zhang decided to reverse the Coens’ direction, making every performance larger than life except the one by M. Emmet Walsh’s analogue. One character’s eyes are permanently crossed; another’s overbite is so exaggerated that acrylic nails appear to have been glued to his front teeth. A husband cuts out the face of a picture of a baby and forces his wife to pretend to be the son they never had. What might sound deliciously weird on paper reads, in practice, as desperation.

I’m avoiding describing the plot, not because I want to avoid spoiling A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop but because I want to avoid spoiling Blood Simple. It’s the premise that launched a thousand noirs – a man suspects his wife of cheating on him and hires a detective to prove it – but the Coens tossed a few wrenches that veer the story into unexpected directions. Zhang may have broadened the tone and moved the setting to 19th Century China, but in terms of story, his take hews tediously close to the original. Noodle Shop romps perfunctorily from plot point to plot point, with none of the suspense or artistry that makes Blood Simple endlessly rewatchable. (Strangely, given his strict fidelity to the source material, the one scene Zhang doesn’t replicate is arguably the original’s most iconic.) If you’ve seen Blood Simple, you’ll be bored; if you haven’t, you owe it to yourself to see the story told with some style. As Blood Simple‘s Meurice might say, A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop is the same old song, but with a different (much less interesting) meaning.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 2009, 2009 movies, 2010, 2010 movies, a woman a gun and a noodle shop, blood simple, mailbox film festival, movies, the coen brothers, zhang yimou | Leave a Comment »

Micmacs isn’t a bad film at all. In fact, it’s got quite a lot of charm. The plot of Micmacs is as much a political wish-fulfillment fantasy as The Ghost Writer, but its outlandishness almost makes it more believable. The actors ably toe the line between zany and overly twee, with the sorts of expressive faces and bodies usually found in the circus, not the cinema. Even the characters who threaten to be one-note (the contortionist, the calculator, the human cannonball) work precisely because there’s no emotional arc or complex characterizations to distract from the story or the visuals. Micmacs also marks the return of director Jean-Pierre Jeunet and his distinctive visual style, a cross between a live-action cartoon and a shot-for-shot remake of an Old Hollywood picture. Jeunet stuffs the film with a dazzling number of ideas, regardless of whether they have anything to do with the story: a do-nothing machine, a pastiche of The Big Sleep, an animated sequence depicting famous weird deaths.

But why, then, does Micmacs fail to leave much of an impression? Perhaps because Jeunet, by making his films so singular, has constructed such a narrow universe that it becomes claustrophobically familiar. All the usual Jeunet trademarks are there, but they’re not as surprising if you’ve seen Delicatessen or Amélie before. That said, there’s something comforting about returning to Jeunet’s universe. Even if you know what you’re getting for Christmas, you can still enjoy the gift. Micmacs is a fun movie, if only to marvel at Jeunet’s ingenuity and skill. But will you remember it the next day? (I barely do.)

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged 2009, 2009 movies, 2010, 2010 movies, jean-pierre jeunet, mailbox film festival, micmacs, movies | Leave a Comment »

I’m a big fan of Noah Baumbach’s first film, Kicking and Screaming, probably because I saw it shortly after finishing grad school. I’m not sure there’s another movie that so squarely gets that post-graduation combination of anxiety and ambivalence, where the freedom to do anything paralyzes you into doing nothing. Sure, The Graduate is a classic, but the kids in Kicking and Screaming are a bit more relatable than a guy having an affair with his girlfriend’s mom. The characters in Kicking and Screaming may be pretentious and self-pitying, but then, aren’t most college students?

Strangely, though, I’m pretty cold when it comes to the rest of Baumbach’s filmography. I found his previous film, the sub-Rohmer character study Margot at the Wedding, actively repellent in its savage navel-gazing, and The Squid and the Whale only slightly less so. Still, hope springs eternal. The trailer for Greenberg looked great. But was it the clips from the movie that had me excited, or just LCD Soundsystem’s anthemic “All My Friends”?

Luckily, Greenberg’s the best movie Baumbach’s directed since the ‘90s. Although the film deals with heavy issues like depression and aging, Baumbach gives it a levity missing from his recent movies. Like Kicking and Screaming, Greenberg is funny, but it’s humor cut with sadness and desperation. Those character traits so endearing in a post-adolescent Chris Eigeman – aimlessness, insecurity, social anxiety – look near-psychotic on a fortyish Ben Stiller. The students in Kicking and Screaming wore their cynicism like they wore their chunky heels and flannel shirts, but Roger Greenberg’s (Stiller) had a few decades to really get bitter. At the film’s start, he has just completed a stay in a mental hospital. He returns to his hometown of Los Angeles to housesit for his wealthy brother’s family. There, he meets with people who remind him of who he could have been, from the girlfriend he should have married (Jennifer Jason Leigh) to the bandmates he let down by refusing to “sell out” (Rhys Ifans, Mark Duplass), all of whom have moved on with their lives in a way he hasn’t. He also strikes up an ambivalent affair with his brother’s much-younger personal assistant, Florence (Greta Gerwig), who’s so empty inside and afraid of being alone that she’s nearly as fragile as Greenberg himself. There are some painful moments in the film where Greenberg denigrates Florence just to make her feel as terrible as he does. Yet Florence continues to give him chances, partly because she’s lonely, but partly because she senses his reactions are a defense mechanism. It’s not pretty, but it’s believable.

Yet Greenberg doesn’t wallow in its depression. Baumbach has written some of his wittiest and most affecting dialogue in years, while the relationships between Stiller, Ifans and Leigh are so lived-in that their problems feel organic, not the product of a screenwriters’ agenda. While the film has a few missteps – Greenberg’s “conversion experience” in the last act is an overlong deus ex machina, and Gerwig’s range is a bit too limited to capture Florence’s emotional arc – at it’s best, it’s a reminder of how good Baumbach can be when he’s firing on all cylinders. Greenberg may still be a distant second to Kicking and Screaming, but try me again when I’m 40.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 2010, 2010 movies, ben stiller, greenberg, greta gerwig, jennifer jason leigh, kicking and screaming, mailbox film festival, mark duplass, movies, noah baumbach, rhys ifans | 1 Comment »

Much has been made of how Pierce Brosnan’s character in The Ghost Writer is a blatant stand-in for Tony Blair. Co-screenwriter Robert Harris (who also penned the novel The Ghost that the film is based on) was a former Blair supporter who became disillusioned with the prime minister’s enthusiasm for the Iraq War. Harris paints a sort of a wish-fulfillment scenario, where Adam Lang (Brosnan) is forced to account for his alleged war crimes, both through a formal trial at the Hague and by protesters congregating at the end of his private drive. Harris also constructs an elaborate conspiracy to explicate how the United Kingdom got pulled into Iraq. After all, when someone you trust betrays you, it’s easier to believe that his hand was forced, not that he simply made a decision you didn’t agree with.

As much as The Ghost Writer can be read as reflecting Harris’s real-life experiences, though, the movie is just as much a product of director and co-writer Roman Polanski. Polanski, probably the most controversial filmmaker whose films aren’t particularly controversial, is one of the last of his generation of auteurs who can still make movies that are both commercially successful and deeply personal. At first blush, a film about a former British prime minister and his ghostwriter seems to have little to do with the Polish director’s checkered history. But Lang and Polanski are both great men in exile, neither of whom quite comprehends the accusations against him. Both have supporters too eager to give them a pass for their crimes, and detractors who refuse to see their good points. Polanski, arrested after leaving the safe haven of France, edited The Ghost Writer while under house arrest in Switzerland. And while Lang isn’t formally accused of a crime until well into the movie, he has nevertheless spent his post-ministerial days in a mansion on Martha’s Vineyard. The US, not so coincidentally, doesn’t extradite people accused by the International Criminal Court.

Polanski gives the film an unusual flat appearance to emphasize the claustrophobia and paranoia of living in a mansion with all modern conveniences, except for real freedom. Yet that distinctive look is also the product of a necessary process, in which the director used green screens to substitute for Massachusetts and London, places where he couldn’t set foot without being arrested. But does The Ghost Writer have anything to say about Polanski’s mental state as a fugitive convict? I’m hesitant to play armchair (or movie theater seat) psychiatrist. I’ll note only that Lang seems to think of himself as an innocent man – not because he didn’t do the things he was accused of doing, but because he doesn’t see them as crimes. I’d have trouble believing Polanski didn’t intend the audience to recognize some shared ground between him and Lang. After all, a major plot twist in The Ghost Writer hinges on Ewan MacGregor’s character discovering a secret message that’s been in his hands the whole time. All he had to do was read in between the lines.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 2010, 2010 movies, ewan macgregor, mailbox film festival, movies, pierce brosnan, robert harris, roman polanski, the ghost, the ghost writer | Leave a Comment »

I never went to an all-girls school, and certainly not a boarding school. I did, however, attend a girls’ summer camp for one month every summer from the ages of 10 to 17. From my experience there (an overwhelmingly positive one, I should clarify), I think I can extrapolate an understanding of the even more insular world of the year-round boarding school. Friendships in isolation accelerate at a faster clip and to a much deeper degree than out in the “real world.” Yet this setting can also intensify an adolescent girl’s worst impulses. The desire to fit in, the distaste for the unfamiliar and an underdeveloped sense of empathy is a noxious combination that, when multiplied across a group, can mutate into a mob mentality. There will always be girls who get hurt, and girls who look back later in disbelief, disturbed at their own indifference and cruelty.

The girls’ boarding school in Cracks is steeped in this atmosphere of intensely polarized emotion. The film starts as a British take on Mädchen in Uniform, the story of a relationship between a beloved teacher and her female students that, in a least one case, may be more than strictly pedagogical. Di Radfield (Juno Temple) is the captain of the diving team and the favorite student of Miss G (Eva Green). At confession, Di admits to “lustful thoughts” about the gardener’s son, but he’s clearly not the only object of her desire. With her smoky-eyed Continental looks and her tales of exotic travels, Miss G is not just an engaging teacher and an attractive role model. She represents the world outside the boarding school and all the promise it holds for her students.

With the arrival of Spanish student Fiamma (Maria Valverde), though, the group’s idyllic existence begins to splinter. The girls are simultaneously fascinated by and jealous of this aristocratic foreigner with a mysterious (and, they imagine, romantic) past. After Fiamma’s elegant somersault pike at her first practice, Di no longer “sets the standard” in diving, and Miss G’s attentions begin to drift toward the new girl. Di, fearful of losing her place within the group, begins lashing out at Fiamma and enlists the other girls to do the same. Meanwhile, Fiamma, unsettled by Miss G’s fascination with her, rebuffs the teacher’s gifts and attention. She is the only student worldly enough to see through Miss G’s bohemian airs and adventure stories as fantasy, and to identify her impulsiveness and intense attachment to her students as something more sinister. The teacher, for her part, recognizes Fiamma as the sophisticate she only pretends to be. “You’re not like the other girls; they’re still waiting for their lives to begin,” Miss G tells her student, though she herself is just as inexperienced. The teacher can relate so well to her students because her emotions are also stalled in adolescence. Miss G desperately sacrifices everything just for her crush to notice her. When she doesn’t reciprocate … well, “cracks” is as much a verb as it is a noun.

Cracks is bound to draw comparisons with Lord of the Flies, although the underlying message is actually quite different. No matter how cruelly the girls treat Fiamma, their bullying comes from a place of petulance and insecurity. Only an adult, the film reminds us, has the capacity for true evil. The final act pushes this theme to almost absurd extremes, but director Jordan Scott never shatters the film’s dreamy yet troubled ambiance. Scott lavishes care on slow-motion shots of the girls diving through the air or dancing together at a secret midnight party, scenes that relax the escalating tension while simultaneously emphasizing the girls’ uneasy intermediacy between childhood and maturity. While (hopefully) few female viewers can relate directly to Cracks’s extreme plot, many more will recognize their own adolescence, refracted as through a shattered glass.

Cracks opens in theaters March 18.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 2009, 2009 movies, 2011, 2011 movies, cracks, eva green, fresh celluloid, jordan scott, juno temple, maria valverde, movies | Leave a Comment »

No other time or place in history has been as well documented as America in the early 21st Century, at least in terms of number of keystrokes. But how much of it will survive the endless cycles of format obsolescence? Even if the Library of Congress still stands a thousand years from now, could future generations decipher our endless Tweeting? Would they want to – would we want them to? Whatever record do leave behind will paint a distorted, incomplete picture – and that’s with us living in a free society in the age of WordPress. Now shift the setting of this hypothetical exercise to a place where the government actively suppressed a group of people and attempted to rewrite their public narrative. Even once this regime was overthrown, its version of history became unwittingly perpetuated for decades.

These circumstances form the background of Yael Hersonski’s documentary, A Film Unfinished. In the early ’40s, the Nazi propaganda department sent a group of filmmakers to shoot footage in Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto. The intended film was never completed, for reasons still unknown. After the war, the Soviets discovered over an hour of the raw film (labeled “Ghetto”) in a Nazi vault. Historians and filmmakers seized on the footage, and clips turned up in Holocaust museums and documentaries as visual evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto.

One problem: not everything in “Ghetto” was what it seemed. In 1998, two more reels of outtakes turned up that cast aspersion on the film’s validity. Some of the original footage captured genuine horrors of a society where death was ubiquitous and the luckiest residents ate a few crumbs a day. But the new footage also proved that much of “Ghetto” had been carefully stage-managed and choreographed. The outtakes reveal take after take of involuntary actors forced to repeat scenes until they got it “right.” Alternate angles show guns pointed at women to force them into a ritual bath, or fired in the air to incite a riot. Hersonski examines the film reel by reel, using the outtakes footage and historical documents to illuminate the inaccuracies. Hersonski then shows the footage to survivors of the Warsaw ghetto, who recoil at the blatant falsehoods onscreen. One survivor recalls the filmmakers bringing horsemeat into the ghetto to create the illusion of a plentiful food supply. Another scoffs at a floral centerpiece on a table, remarking, “We would have eaten the flowers.” In between these scenes, Hersonski includes a reenactment of an interview with German cameraman Willy Wist, the only person ever successfully identified as having worked on “Ghetto.” Wist admits the filmmakers’ deception, but claims not to have understood the purpose of the propaganda film, or to have known that the ghetto’s residents would be evacuated to the Treblinka extermination camp a few months later.

The message “Ghetto” intended to convey is not readily clear, which is likely why it was never finished. Staged scenes of well-dressed Jews at a dinner party are juxtaposed with beggars and corpses littering the sidewalks. Most likely it was meant to show the contempt that “better-off” Jews felt for their suffering counterparts – even though everyone in the ghetto struggled to meet their basic needs. Fortunately for the film, a few elderly survivors are still around to refute the footage. But what if the Holocaust weren’t in living memory, or what if the Nazis had triumphed in World War II? At its most basic, A Film Unfinished serves as further proof of the old adage “don’t believe everything you see.” More disturbingly, though, the film is also a dark reminder of how unstable our concept of “history” really is.

Posted in Say/Think | Tagged 2010, 2010 movies, a film unfinished, das ghetto, documentary, mailbox film festival, movies, yael hersonski | Leave a Comment »